21 Mar St. George Creaghe as Sheriff

I had always heard stories of my great-grandfather, St. George Creaghe (1852-1924), being sheriff of Apache County, Arizona Territory. However, it was never clear just what that meant. The only frames of reference were Western Movies, TV shows (there were plenty in the 1950’s; it was the predominate genre) and comic books. In these portrayals it seemed as though all the sheriff did was sit in a chair on the wooden sidewalk outside his Main Street office and wait for something to happen. Then he would face down the bad guy in a duel in the street, win, and justice would prevail.

Questions arose: “Was it like that for St. George?” “How did he get the job?” “What other duties did he have?” “Was St. George really a part of the “Wild West” or not so much?” “Where did he line up with the iconic figures of that era?”

Let’s see if we can find out. First, a brief look at the history of the American Southwest before and during the Creaghe family’s time there is necessary for a complete picture. Of course, the entire story of this quite colorful, interesting, and remarkable time is well-beyond the scope of this project. The principal reference used for this article is “Desert Lawmen – The High Sheriffs of New Mexico and Arizona, 1846-1912.” All page number citations refer to this book.

The area that now makes up the states of California, Arizona, and New Mexico was first a part of New Spain and then Mexico until 1848 when the U.S. defeated Mexico in the Mexican War – or Conquest, depending upon your point of view. Following the principle of “Manifest Destiny,” U.S. President James Polk more or less created a war with Mexico in 1846 over a border dispute. With the defeat of Mexico and $15 million, plus the Gadsden Purchase (another $10 million) in 1854, these lands and their citizens passed to the United States and became the territories of California and New Mexico. California became a state almost immediately. Arizona was eventually split off from New Mexico and recognized as a separate territory in 1863.

General Stephen Watts Kearny’s forces occupied Santa Fe in 1846, and the general imposed a U.S. style of government and law enforcement in place of the existing Spanish-Mexican structure (pg. 1). Charles Bent was appointed as the first governor; and he, in turn, appointed the first sheriffs; one of whom was James Hubbell, father of John Lorenzo Hubbell (see “Bazan Family History”).

The “Kearny Code” proscribed the traditional duties of sheriff to include the following duties (pg. 7):

- Serving warrants, subpoenas and other writs of courts in their counties. Apparently Spring and Fall court sessions were very busy times for the sheriff’s office.

- Preserve the peace.

- Keep the jail.

- They could summon a “posse comitatus” (power of the county) from all the able-bodied males in the county.

- Tax collector.

Initially the sheriff was to receive a salary of $200 annually in addition to percentage of fees collected. These fees might include (pg. 7):

- Serving a warrant – $1.00

- Summoning a witness – $.50

- Committing a prisoner to jail – $1.00

- Feeding a prisoner (daily) – $.25

- Execution of death warrant – $15.00

- Travel (per mile) – $.05

In the beginning, at least, these fees provided the primary source of income. But, by 1885, many of the counties had moved to a salaried position for the office of sheriff. Apache County paid John Lorenzo Hubbell $5,000 annually that year (pg.286).

With territorial status in 1850, the office of sheriff took on its “modern form.” Formal U.S. traditions were imposed by Congress removing most, but not all, of Kearny’s accommodation to Mexican institutions (pg. 8). Then followed a period of adjustment as the new system matured. The Hispanic citizens became accustomed to it, the boundaries of the counties and New Mexico Territory itself were further defined. Finally, in February 1863 the western half of the territory was broken off and became the Territory of Arizona.

Some of the initial counties were vast – 300 by 800 miles. With time, immigration, and organization, more counties were created and were more manageable for a man on horseback. In 1885, roughly the western half of Apache County was split off and reorganized as Navajo County (pg. 283 & Wikipedia). When St. George was sheriff in 1889, Apache County comprised of 21,177 square miles (greater than the area of New Hampshire and Vermont combined).

Things were disrupted a bit by the American Civil War when Confederate forces (Texans) occupied a good part of New Mexico Territory in 1861. However, this was short lived, and they were gone by April 1862. The next year Congress granted Territorial Status to Arizona.

Both territories were quite multicultural – New Mexico more so than Arizona – with Hispanic, Anglo and Native American (Indian) populations. This, of course, led to difficulties as might be expected. Many of the people who were successful in the early days assimilated into this multicultural milieu quite well – the Hubbell family and St. George Creaghe for example.

The Hispanic influence in Arizona was not as strong as in New Mexico, in that of the thirty-eight men who held the sheriff’s post before 1880, only one was Hispano. That man, Alejandro Peralta, was appointed the first sheriff of the newly created Apache County in 1879 by the Territorial Governor John C. Fremont. At about the same time, the governor also appointed a non-U.S. citizen, Irish immigrant with an Española wife as one of the first County Supervisors of the same new county. That man was St. George Creaghe.

Arizona Territory was quite sparsely populated, by non-Native American settlers at least, with the 1880 census showing 40,440.

Before moving any further in this process, some definitions are in order:

The office of the sheriff in those times was responsible for duties that encompassed an entire vast county; but, as things organized and more people settled in the region, smaller counties were created, and the area of responsibility for sheriff became more manageable. Some of these countywide duties were enumerated earlier.

Law enforcement of a town or city was the purview of the Town Marshall – analogous to a Chief of Police today in the U.S.

Federal law enforcement throughout a territory was the responsibility of a United States Marshall and his deputies. There were very few in an entire Territory. U.S. Marshalls and County Sheriffs were more or less equal and tended to co-operate well together (p.49). Movies and television had sometimes made these distinctions unclear; perhaps because it was unclear to the writers.

The office of Sheriff and its two-year-term was considered “a great prize on the southwestern frontier” (pg.74) and was one of the few good political jobs available to those with political aspirations. Local politics in all their aspects were very important in the Territories because the population (male only population, that is) could not vote in most federal elections. As a result, they turned their enthusiasm to contests such as Sheriff. Evidently, the candidates were creative and enthusiastic in their campaigns. There is no evidence regarding how St. George campaigned.

Law and order was a frequent campaign theme. A certain competence with firearms was assumed, but voters were “more concerned that the candidates possess nerve and determination to use their guns (p. 53)” rather than have a history of having killed a man. Posse experience was valued in a prospective sheriff; St. George presumably had that in the events surrounding his brother’s death. Poor judgement and intemperate behavior could ruin a man’s chances. Tómas Perez, Sheriff of Apache County, 1883-84, was not re-elected in 1888 because two of his former deputies were in prison. Presumably the incumbent, Commodore Perry, also ran in that election, but the good people of the county elected the thirty-six-year-old St. George Creaghe instead (see “Posse”).

Understandably, sheriff’s “most disliked the task of hanging condemned men p. 47).” Of the 51 legal hangings in the Arizona Territory, none occurred in Apache County. Presumably, St. George was pleased about that. There were, however, fifty-three people lynched by vigilante action in the territory. Three happened in Springerville in 1877, two in St. John’s in 1881, and three more in Tonto Basin in the far south of Apache County in 1888. While none of these were during his terms of sheriff, he must have known of at least the first five. These were interesting times.

One of the most common duties of the position was keeping the peace. It could be as routine as dealing with public intoxication, but nothing could be taken lightly. In spite of the risks, some sheriffs eschewed the use of firearms. There is no record of St. George’s stance on this issue, but significant wear on the grip of his pistol shows that it was worn a great deal (see “Artifacts – St. George Creaghe’s Pistol”).

His friend and wife’s distant cousin, John Lorenzo Hubbell (Apache County Sheriff, 1885-1886) apparently avoided using guns, preferring persuading miscreants to surrender “in his usual calm, quiet way (p.91).” This style was the exception; not the rule.

Commodore Perry Owens, St. George’s immediate predecessor and a man he must have known well, walked into an incident when trying to arrest a rustler in 1887. He ended up killing three and wounding one more in a shootout. Although controversial, as these things tended to be, it cemented Owens’ reputation as a gunfighter.

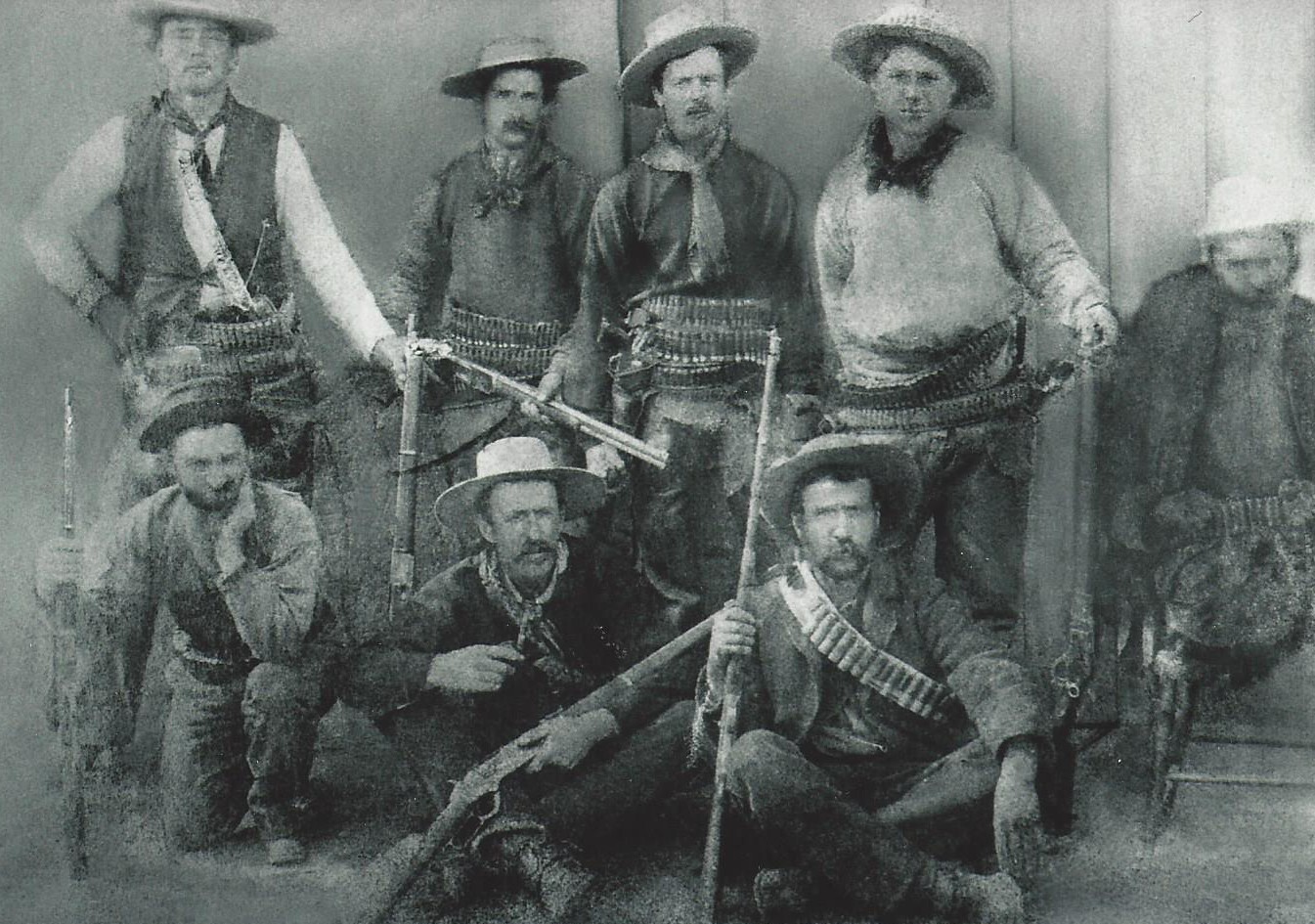

Virtually nothing is known specifically about St. George’s career as a sheriff. There are pictures of him with two groups of heavily armed men, presumably posses of some kind, but it is not clear if they are part of actually deputized group (see “Posse”).

However, there is one story. In the late 1950’s, after I finished mowing her lawn St. George’s daughter, Ethel Corning, née Creaghe (1889-1966) told me of an incident in response to my question about her father as sheriff. As best I can recall the story went like this:

The family was sitting in parlor of their house when she noticed a pistol in someone’s hand passing between the curtains of an open window. Serapia saw it, screamed, and pushed the gun aside. No shot was fired, but the man fled down the street on horseback. St. George bolted out the door, mounted his horse and gave chase.

A story told by Ethel’s son, Charles, corroborates this tale. There were no other details and none of her grandchildren that I have asked about it are familiar with the story. It could have occurred during his second term when Ethel was about eight years-old. Has a ring of truth about it; I think.

According to Larry Ball, in his book Desert Lawmen, “in spite of the dangerous nature of shrievalty, surprisingly few occupants died in the line of duty.” St. George may well not have agreed with that statement. On the Arizona Peace Officers’ Memorial, there are 26 names of members of Sheriff’s Offices (both sheriffs and deputies) who were killed in the line of duty during territorial days (see “Sites”); one of them was his younger brother, Gerald (Paddy) Creaghe.

Pursuing fugitives over long distances was one of the roles of the frontier sheriff. The long, remote border between New Mexico and Apache County, Arizona was particularly burdensome to St. George and his fellow Apache County lawmen. One of the problems was funding for pursuit into New Mexico. This provided a significant advantage to the criminals. In 1890, during his first term, the Apache County Board of Supervisions would not pay the expenses of pursuing and extraditing a fugitive, E.W. Nelson, from New Mexico. This led St. George to express his frustration in letter to Territorial Governor Lew Wolfley, the same year. “If there is no pay for running down criminals that cross the Territorial Line, he grumbled, “the criminal is in luck” (p. 218, full letter in genealogy book)

One reason that the shiveralty was such a plum job in territorial days was the fact that the sheriff also had the “ex officio” responsibility for tax assessment and collection. While this took significant time, the sheriff was allowed a fee of up to five percent. By 1891, this was reduced to one percent in New Mexico, but it was still felt that the sheriff would still be provided with a “comfortable” living (p. 263). Eventually, this duty was removed and completely removed from the office’s responsibility.

By 1884, a salary system had instituted in the larger counties. That year, John Lorenzo Hubbell was paid an annual salary of $5,000 (p. 286). Seems quite good for the time and place. This amount may be equivalent to a purchasing power of $135,000 in 2019 U.S. dollars (www.measuringworth.com). It seems as though St. George, who followed Hubbell in the office four years later, and his family were rather comfortable in that the ranching income did not stop (most sheriffs kept their day jobs) and some other fees were allowed.

In Desert Lawmen, Larry Ball draws some interesting conclusions about the men who filled the role of sheriff in the American Southwest during Territorial days. One of the statistics that stands out is the fact that there were so few of them. In the two territories together, a total of only 504 men ever held the office. In Arizona, there were only 155 total. Starting with the seven appointees in 1846, there were forty serving when the period came to a close with statehood in 1912. When St. George served his first term, 1889-1891, he was one of only eleven sheriffs in Arizona Territory; in 1897 he was one of thirteen (p. 346) – a remarkably small number to provide this vital service to this vast, predominantly rural area.

As opposed to New Mexico, the Hispanic population controlled the vote in only two Arizona counties, Apache and Navajo. St. George was the only man to win election twice (1889 and 1897) in Apache County except for Sylvestre Peralta who served out the last eleven years until statehood. While competence was probably a major factor in his success, the fact that his wife, Serapia Bazan, was of a Spanish Family with centuries old roots in the Territories certainly did not hurt his chances.

Personal information is available for 168 of the 504 sheriffs and, from that, a typical sheriff can be inferred (p. 301). The list below will show how St. George matches up:

Property Owner – required for office. 47 owned ranches – he had a ranch near Springerville.

Military Service (42) – No.

Other Political Office (52) – Yes, County Supervisor in 1879. Assessor and Treasurer,

Previous Peace Officer (39) – Had it for second-term.

Membership in Benevolent Order – Masonic Secret Society

County of Birth (104 USA, 3 Ireland) – Ireland

Family History of Law Enforcement – Not an actual category, but St. George’s grandfather, Richard Creaghe, was the High Sheriff, County Tipperary. His brother, Gerald, was a Deputy Sherriff, Apache County in 1879.

These Territorial Sheriffs of the American Southwest may have represented the apex of their particular brand of law enforcement – an amateur lawman in a relatively lawless land (p. 307). Although the office of sheriff persists into the 21st Century, most, if not all have been replaced by professional peace officers.

James Corning (1919-2000) quoted Serapia (1835-1936), his grandmother, as saying “eastern Arizona was the last refuge of the outlaws (Corning).” The Territorial Southwest was also the home of many of the legendary lawmen of the Old West, many of whom have been immortalized in print, Western movies and television shows of the 1950’s. These men can be considered peers of St. George:

John Slaughter (1841-1922) – Sheriff, Cochise County, South of Apache County, 1886-1891. “Texas John Slaughter “Disney T.V. Show – 1958-1961.

Elfago Baca (1865-1945) – Deputy Sheriff, Socorro County, New Mexico, 1884, Albuquerque, 1886, Private Detective, 1890. “Nine Lives of Elfago Baca.” Disney mni-series 1958.

Wyatt Earp (1848-1929) – Deputy Town Marshall, Tombstone, Cochise County, Arizona, 1879-1881. “Gun Fight at OK Corral” with brother Morgan and Virgil Earp and Doc Holliday, 1881. “Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp.” T.V. Show, 1950-1961. Far too many movies and books to list.

Tom Horn (1860-1903) – Deputy Sheriff in Gila, Yavapai, and Apache Counties in late 1880’s – probably under Commodore Perry Owens. Hung for murder in Wyoming in 1903. Multiple movies and T.V. shows.

Pat Garrett (1850-1908) – Sheriff of Lincoln and Doña Counties, New Mexico. Killed outlaw Billy the Kid in 1881. Movies and T.V. show too numerous to list.

Commodore Perry Owens (1852-1919) – Sheriff of Apache (1887-1888) and Navajo (1895-1896) Counties. Killed three men during attempted arrest in Holbrook 1887. Legitimately earned title of “gun fighter.” Books, no movies.

Ike Clanton (1847-1887) – One of the loosely associated outlaws known as “The Cowboys” who fought the Earps at the OK Corral in 1881. Had a ranch east of Springerville at the time of his death in 1887 at the hands of Apache County deputies. Character in multiple T.V. shows, movies and books.

John Lorenzo Hubbell (1853-1930) – Sheriff of Apache County, 1885-1886. Relative of Serapia Bazan Creaghe, major figure in territorial politics and as an Indian Trader.

So, did St. George actually know these guys? Well, he certainly knew Owens and Hubbell and probably at least knew of Tom Horn. He had to have heard of Slaughter, Baca and the Earps if not having actually met them. Pat Garrett was at the “legend in his own time” level and certainly known in law enforcement circles, if not exactly respected. There is a good chance that they, too, knew of St. George.

The notorious Ike Clanton was probably also known to him in that the outlaw’s ranch was near St. George’s operation also east of Springerville – “near Coyote Spring, east of Round Valley (Springerville) “(Crosby). Wonder if their paths crossed?

One question that comes up when discussing a sheriff in the old west is whether or not he ever used a gun in pursuit if his duties. Thus far, I have found no evidence that St. George did; however, there were posses formed from time in his area of which he was almost certainly part. There is the story of the posse that responded to Gerald Creaghe’s death in 1879. In a scrap book kept by Percy Creaghe’s family, the group is incorrectly credited with “exterminating Victorio and his band” of renegade Indians (See “Ancestors” and “Posse”). In that scrap book, an article is cited from the Arizona Democrat Tuesday, June 22, 1880. It would be most helpful if that article could be found.

As can be seen, St. George actively participated in a remarkable time in the history of the American Southwest. He did his job well in that he was elected to a second term, which was unprecedented in Apache County until the last Territorial Sheriff who was elected in 1903 and served for eleven consecutive years. He was a peer of some of the most well-known figures in U.S. History. St. George was the real thing.

Stephen B. Creaghe, March 20, 2019

References;

Ball. Larry D., Desert Lawmen, University of New Mexico Press, 1992.

Cottam, Erica, Hubble Trading Post., University of Oklahoma Press, 2015.

Corning, Charles, Stories collected by Michael Gordon Moore, 2018.

Crosby, George H., St. George and Paddy Creaghe, The St. Johns Observer. August 24,1924. Wikipedia: Apache County and Commodore Perry Owens.

John W Corning

Posted at 16:13h, 14 JuneSt George creaghe was my great grandfather.. His daughter Ethel was my grandmother

Very proud of my heritage.. Great write up.