04 Sep JOHN O’DWYER CREAGHE

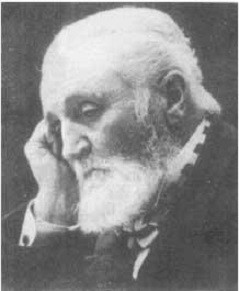

JOHN O’DWYER CREAGHE

1841 – 1920

John O’Dwyer Creaghe led a life filled with adventure, conflict, revolution, and, finally, mental illness. Some parts of his past are somewhat blurry; some are well-documented. This sketch will lay out some of what is known, possible, or not known.

John’s father, Stephen William Creaghe (1805 – 1854) was the eighth of nine children born to Richard Creaghe DL and his wife Matilda Parsons. Thus far, there is little factual material gathered about Stephen’s life. He was, presumably, born and raised at the family estate, Castlepark. On August 21, 1829, Stephen married Sarah Selina Persse (b.~ 1805), daughter of Henry Safford Persse of Galway who was part of the family who held Roxborough House and Estate, near Galway, Ireland. Roxborough House was the seat of the Anglo-Irish Persse family for 250 years. These holdings would indicate a quite well-to-do family, although as the fourth son, Henry had to earn his own living Across the road from Castlepark is a significant parcel of land known as Persse’s Lot. Perhaps Stephen and Sarah met through that proximity – not exactly “the girl next door,” but maybe.

The couple live in Dublin where he worked in the Postal Service and they raised eight children. One of these was John O’Dwyer Creaghe, born November 15th, 1841. Interestingly, Helen Gordon Moore found nothing regarding John when she compiled the Creaghe family genealogy book, which was based on information collected before 1998. Even though internet resources were not what they are today, she did find information on his siblings. Perhaps his controversial, peripatetic life may have led to him being lost to the family; perhaps even disowned.

We have no credible information about him until May 16, 1865, when he arrived in New York. Three months later, August 10, he enlisted as an Assistant Surgeon with the 122nd Regiment, United States Colored Infantry. This was shortly after the end of the American Civil War, April 9,1865. Each regiment had a Surgeon and an Assistant Surgeon assigned to it. John’s position had a rank equivalent to First Lieutenant. Interestingly, the position required a medical degree from a reputable medical college. John did not appear to have a degree until he was discharged. The twenty-three-year-old served with the unit until he was discharged almost a year later on August the 2, 1866. Just after John joined the unit, they were moved from Virginia to the extreme southwestern corner of Texas-Brownsville. Perhaps they were there as occupation forces in the defeated Confederacy, or possibly as a part of the Indian Wars or border security in the post-war period. The 122nd was disbanded in February 1866. John was not discharged until six months later. It is not known what his duties, if any, were from February until August. In fact, he seemed to be doing several things not related to the Army. The twenty -four-year-old did file a Naturalization Petition in Massachusetts on February the 8th and was granted U.S. Citizenship on July the 23, 1866. Alex Trouton speculates that this may have been a reward for his Army service. Perhaps his experiences as an Irish immigrant and serving in African American unit helped shape his future political views.

The African American Civil War Memorial in Washington DC honors the over 210,000 members of the United States Colored Troops and their 7,000 white officers. John’s name is inscribed there on plaque D-125 with the other members of the 122nd. (See “Historic Sites”)

Before his discharge in August, he seemed to have spent time traveling around the northern New England area. He was back in Ireland soon enough after his discharge to present his qualification for certification as a Licentiate of the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (LRCS) in 1866. This designation indicated that the practitioner had not had a formal university medical education, but rather a practical experience such as John’s year as an Assistant Surgeon in the U.S. Army. The next year he was practicing in Mitchelstown, County Cork, about thirty-five miles from Castlepark and Clonmel. One wonders if he had any contact with his uncle, Richard F. H. Creaghe or his younger cousins Richard, Harry, Phillip, or any of his other six cousins in that family.

John earned full certification as a medical practitioner from King and Queen’s College of Physicians in Ireland two years later in 1869. The next year, at age twenty-eight, he married Margaret Slattery (b. 1838) of Waterford and later Gloucestershire, England in a Catholic ceremony in Liverpool, July 29th, 1870. Her father, Pierce, was a merchant. Presumably they returned as a couple to Mitchelstown where John practiced until 1874. Very little else is specifically known about her.. She was not mentioned in any of the biographical pieces that were consulted recently. However, the 1895 Argentine census was recently found to have listed Margaret and John as living in the country.. (Whelehan) No children were mentioned: Margaret and John were fifty-seven and fifty-four years old at the time. From this information, reasonable suppositions can be made: Margaret probably did accompany him on at least some of his extensive travels although her name does not appear on passenger lists with John (Touton), and they did not have children. Her date of death is not known, but it was somewhere between 1895 and 1920 when John was listed as a widower on his death certificate. (Grande)

At age thirty- three, John entered the phase of his life for which he is best known. Sometime in 1874 he emigrated to Buenos Aires. . It is not clear if Margaret accompanied him on this trip to Argentina. With his arrival there, he became what we would call today a “social activist.” His philosophy was that of an Anarchist. I am not knowledgeable regarding the principles of anarchism, but it is based on supporting the rights and place in society of workers and the poor. It seems to be quite close to socialism and communism. There were some pretty radical ideas being put forth in those days. It is not clear why he chose Argentina. In fact, he did not become politically active until fourteen years later in 1888 when he began publishing articles in the journal La Verdad. It is thought that John came under the influence of an Italian anarchist, Errico Malatesta, who lived in Argentina from 1885 to 1889. At this time, Dr. Juan Creaghe’s involvement in the movement was limited to writing articles. Later that would change.

In 1890, the now fort-four-year-old and, presumably, Margaret returned via Dublin to Sheffield, England where he continued to practice medicine. This time he practiced in a poor, working class, heavily Irish district of the city. From the beginning, he was involved in social politics. Initially he joined a local branch of a socialist movement, but they broke away in 1891 to form an anarchist group, which was quite active and aggressive in putting forth their ideals.

John began a newspaper, The Sheffield Anarchist with one Fred Charles. A year later Charles was sentenced to ten years in prison for involvement in an anarchist bomb plot. John was not implicated, but the newspaper’s aggressive stance and John’s activism led to the paper losing readership and eventually folding. Later John was involved in a “No Rent” demonstration against landlords. This time he took up a poker against bailiffs who were trying to stop the disorder. This gained him considerable fame and support with the Sheffield working class. Anarchists, including John, felt that actual revolution was the way forward and were actively promoting violence as a means to their end. In 1891 he wrote, “Give me anarchists who will die NOW if necessary for anarchy…” (O’ Catháin).

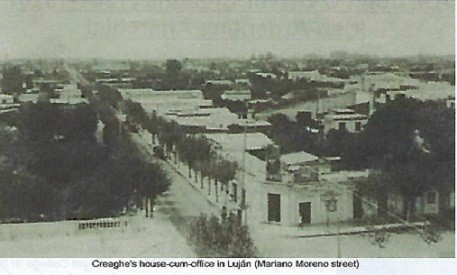

The next year,1891, he returned to Argentina with stops along the way in Liverpool, London, and Spain. The couple settled in Luján, just west of Buenos Aries. There John was instrumental in starting a publication, El Oprimido, (The Oppressed), which ran from 1893 until 1897. It evolved into La Protesta Humana that in turn evolved into the important La Protesta in 1903. La Protesta has been in operation ever since in various forms. These ventures contributed to the formation of the “Mighty Union,” The Federation Obrera Regional Argentina(FORA) – Argentine Regional Workers’ Federation. This was the first national labor confederation in the country.

John was involved with unorthodox educational experiments in Buenos Aires with the Free School movement and was the Director of the Rationalist School in his home city, Luján. All this time and going forward, John continued to practice medicine from his home on the corner of Mariano Moreno and San Martin streets across from the Plaza Colon in Luján.

In 1903 he was back in Buenos Aires fomenting unrest. This time with a revolver instead of a poker. John was resisting the police who were trying to stop the printing and distribution of La Protesta. Although he never actually leveled his pistol, the sixty-one-year-old revolutionary stated, “To loot the printing press, they would first have to step over my corpse.” (Grande)

In 1911 John returned to the United States from Buenos Aires on the SS Vasari via Ellis Island. Eventually, he made his way to Los Angeles where he became associated with the Mexican Anarchist movement and became involved with yet another radical publication, La Regeneracion, which supported the Mexican revolution He became close friends with a leading Mexican anarchist, Ricardo Flores Magón (1874 – 1922). At some level, John was involved in the Magónist Rebellion in Baja, California the same year. John and Ricardo were both supportive of the Mexican Revolutionary, Emilio Zapata, and the Mexican Anarchist movement through their efforts on behalf of the Parido Mexican Liberal Party (PLM). They were involved through the end of the Mexican Revolution in 1914 and continued their activities throughout World War 1.

These were very committed people. Ricardo Magón, an interesting person in his own right, published anti-war writings which got him in trouble with the U.S. Government. In fact, he was convicted of sedition under the Espionage Act in 1917. The thirty-three-year-old was given a twenty-year sentence to be served at Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary in Kansas. In actuality, this was a life sentence; he died in 1922.

John’s life from this point is not well-documented. He did travel back to Argentina at some point and returned to the U.S. in 1915. Older biographical sketches have John dying in prison in Washington, D.C. in 1920. However, Alex Touton and Nicolas Grande found evidence that he, in fact, died on February 19, 1920, in the State of Washington, U.S.A. The elderly doctor and activist had become penniless, homeless and in some way mentally ill – possibly dementia or a frank mental illness of some type. At his death he was an inpatient at the Western State Hospital, a psychiatric hospital, on the site of old Fort Stellacoom in what is now Lakewood, Washington near Tacoma in Pierce, County.

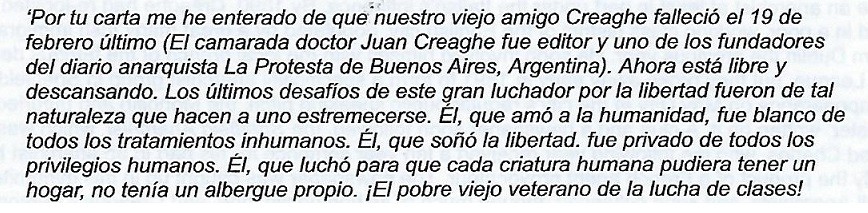

The treatment and care of patients at this hospital may well have been progressive by early 20th Century standards, but it was primitive by today’s standards. This was before pharmacologic treatment and modern “talk therapy.” Ice water baths, locked wards, overcrowding and poor sanitation were common in some facilities. It’s not clear what therapies John received at Western State. Medical records have not been obtained, if they even exist at this point. We do have some insight, however. His friend Ricardo Magón wrote from his cell in Leavenworth about John’s situation when he was informed of his friend’s death:

“Your letter informed me that our friend Creaghe died last February 19th (Dr. Comrade John Creaghe was the editor and was one of the founders of the anarchist newspaper La Protesta de Buenos Aires, Argentina). He is now free and resting in peace. The last challenges of this great fighter for freedom were such that they made one shutter at the thought. He, who loved humanity, experienced the most inhumane treatments. He, who dreamt of liberty, was prevented from enjoying the most humane privileges. He, who fought so that each human creature had a shelter, never had his own. Poor old veteran fighter of the class struggle!” (Translation by Noëlie Creaghe)

John was probably buried in the hospital cemetery along with over 3000 other patients. Commonly hospital burials in those times were, at best, marked with a small numbered concrete block. Efforts to refurbish the cemetery and identify these graves have been undertaken by the Grave Concerns Association. As of 2011 they had a database of over 3600 names. John’s name was not among them. It has not been possible to contact the Association thus far.

As is often the case, investigation often raises more questions than it answers. Hopefully his final resting place can be found. He certainly deserves that much.

Stephen B. Creaghe, August 24, 2021.

Authors Note:

When searching the internet several years ago for other information, John O’Dwyer Creaghe’s name came up, but there was no information that I had seen linking him to our family. At that time, I did not pursue it. Then in January 2020, an inquiry from the Luján, Argentina journalist, Nicolas Grande, expressing a significant interest in John’s story, was received. In fact, Nicolas has written articles about John’s life and is working on a book at this time. With his information a connection was established to our family. Coincidentally, six months later Alex Trouton of Anglo-Irish decent who lives in London, contacted the CFHS website for information. She was constructing an extensive family tree for the Patterson-Trouton family. Her research showed that her 3X great-uncle, William Burke (1816 – 1908) married Anne Creaghe (1831 – 1919), John’s older sister, on June the 4, 1858. Nicolas and Alex corresponded, and more information was forthcoming. More recently, Niall Whelehan of the Department of History, University of Strathclyde in Glasgow, wrote with census information regarding John and Margaret. He has a book, Changing Land, Diaspora Activism and the Irish Land War, due out in December 20121. which features a chapter on John. He is also planning a book length study of John’s life.

Michael Gordon Moore was simultaneously and independently putting together a Family Chart for Descendants of Nicolas Creaghe. He had even more information, some recorded in Latin. Their work formed the backbone of this brief sketch of John O’Dwyer’s Creaghe’s life. My thanks to them, and any mistakes are mine.

SBC

References:

Alexander, Richard, With The Poor People Of The Earth. A Biography of John Creaghe of Sheffield and Buenos Aries by Alan O’Toole {A Review}, Kate Sharply Library, London and Berkeley, 2005.

Catháin, Máirtin O, Dr. John O’ Dwyer Creaghe (1841-1920), Irish-Argentine Anarchist, Society for Irish Latin American Studies, 2008.

Grande, Nicolas, Juan Creaghe: vida de pelicula que se apagó hace 100 años (John Creaghe: movie-like life that died out 100 years ago), Seminario de la ciudad de Luján. July 2021.

Grande, Nicolas, Communications and references.

Roster of Civil War Surgeons and Assistant Surgeons – Medical Antiques (https://www.medicalantiques.com>Antiques_on_books).

Trouton, Alex, Communications and references.

Washington State Archives – Digital Archives, Short form Death Record for John Creaghe

Whelehan, Niall, Communications.

Wikipedia, African American Civil War Memorial and Museum and multiple other references.

No Comments