08 Jun Richard F.H. Creaghe and Anna Maria Archer-Butler Creaghe

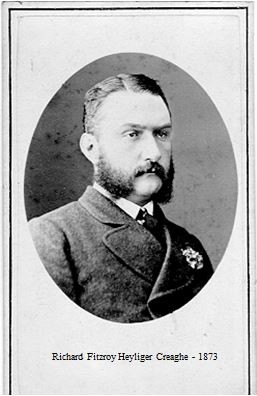

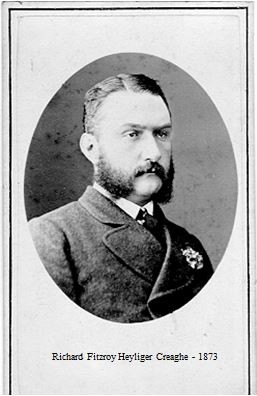

Richard Fitzroy Heyliger Creaghe (1804 – 1890)

and

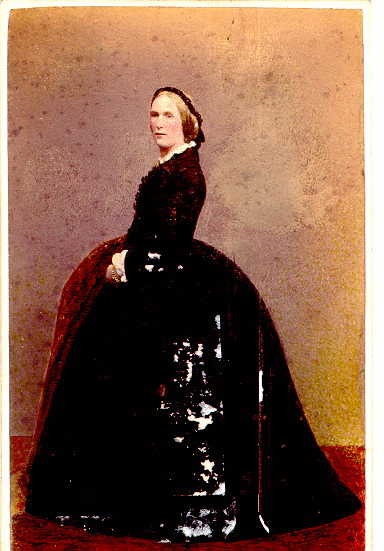

Anna Maria Archer-Butler Creaghe (1823 – 1903)

Family Chart: Generation 7, #20

Richard Fitzroy Heyliger Creaghe and his wife, Anna Maria Archer-Butler, lived in some of the more dynamic and unsettling times in the history of Ireland. They were both part of the “Landed Gentry” and lived comfortable lives. For instance, they would not have been directly touched by the Great Famine of 1846 – 1848. They were, however, quite prescient about the future Ireland held for their sons and made difficult decisions regarding their sons’ futures. They also had the resources to make things happen.

On July 28, 1804, Richard was born to Richard Creaghe, D.L., and Matilda Parsons Creaghe of Castlepark near Golden, Co. Tipperary. He was named after his father, joining what became a long, uninterrupted line of other Richards. It can, in fact, become confusing as to which Richard is being discussed. Therefore, unless otherwise indicated, assume the subject is Richard F.H. Creaghe. It is not clear where the Fitzroy came from – perhaps from his mother’s line; Heyliger was his grandmother’s maiden name.

He was the seventh of nine children; third of four sons who survived infancy. By the time of his birth, his parents had been living on the estate for at least nine years, and, presumably, things were going smoothly at Castlepark. What his childhood was like is not known. One can imagine that it could have been a great environment for a boy to grow up. His father was a part of the Landed Gentry class, had significant land holdings (Castlepark and other properties were probably about 2,700 acres), and enjoyed a comfortable income. There were fields to roam, horses to ride, and the Suir River just down the slope in front of the house for fishing and throwing rocks. He would have had schooling, but just what and how much is not known. There is a paucity of information about Richard and Anna Maria’s lives, but some extrapolations can be made.

We can only speculate what his relationships were with his surviving seven siblings, some of whom were significantly older. He was closest in age with his brother Stephen (1805 – 1852), one year younger, who went on to sire John O’Dwyer Creaghe (1841 – 1920). However, the most consequential relationship was with older brother, Laurence (1797 – 1852), who eventually became the owner of Castlepark. That comes later in our story.

It is apparent that Richard D.L. was concerned about his ability to provide a livelihood for our Richard, his second-oldest surviving son, through his land holdings. In April 1822, he started the process of purchasing a Half-Pay Commission for young Richard in the British Army. This involved enlisting various persons of influence to help with the cause. It took four and a half years and cost £450. On January 7, 1826, Lt. Gen. Taylor notified them that H.R.M. (Queen Victoria) “has been pleased to have Richard Fitzroy Heyliger Creaghe appointed to a Half-Pay Ensigncy” (P.C. Papers, p. 25).

This was good news for the 22-year-old Richard, but a Half-Pay Ensign had no future if he was not attached to a regiment. Therefore, more efforts were applied to that end. On August 8, 1826, Richard D.L. received a letter from the commander-in-chief’s office, Horse Guards, informing him that his son, Ensign Creaghe, “has been restored to Full Pay in the 58th Regiment [58th Rutlandshire Regiment of Foot]…” By October, the two Richards were in Dublin purchasing uniforms.

The 58th deployed to Ceylon (Sri Lanka) in 1828. In January of the next year, the 24-year-old Richard was suffering from a chronic leg ulcer. Percy Creaghe puts forth varicose veins as a probable cause, unusual in a young person, but possible. Whatever the cause, a tropical environment in the 19th century was not conducive to healing a chronic ulcer. The regimental surgeon stated that the patient should return home. By September, he was on his way in a ship called The Africa, stopping at Mauritius, where another military surgeon, James Barry, agreed with the diagnosis and plan. He also referred to Richard as “Lieutenant Creaghe”. At some point, he had been promoted.

It appears that on arrival in Ireland, Richard reverted to half pay. He must have recovered well, because in December 1829, the process of “purchasing a Company” had begun. In May 1830, Richard’s grandmother, Anne Heyliger Creaghe, put in escrow of £1,100 for the endeavor. In January of the next year, he was restored to full pay. It seems that this time, he was now with the 37th [1st North Hampshire] Regiment.

In November 1832, the lieutenant was ordered to take a small detachment from their barracks at Ballincollig (near Cork) to provide security for the “Civil Power in collecting the Tithes” for which a Mr. Cross was in arrears.

The efforts to obtain a company continued through 1835. In February, Richard again left the army on account of ill health. That may not have stopped the effort to purchase a company. Percy Creaghe states, “Grandfather Creaghe was always known as ‘The Captain.'” I think there is little doubt that he did succeed at least in purchasing his company, even if only at Half-Pay.” Interestingly, an 1874 article in a New Zealand newspaper announcing the marriage of Richard’s son (Richard Fitzroy) refers to Richard as a Major in the 37th Regiment.

I think we can conclude that military service was a significant part of Richard’s life plan, not unusual for a second son of gentry. It should be noted that Richard’s younger brother, Stephen, was initially sent to Trinity College in Dublin with plans for “The Cloth” as a career.

Richard’s time in the military may have accounted for his relatively late-in-life marriage at age 38.

When Richard was 19 years old, in 1823, Anna Maria Archer-Butler was born to Piers (Pierce) Archer-Butler and his wife, Anna Maria Gallway, somewhere in the Waterford-Lismore Diocese. I have found nothing regarding Anna Maria’s life prior to her marriage. It can be reasoned that the family probably lived in the Waterford area, since she and Richard resided there or at various locations nearby during their married lives. One wonders how they met in the first place, but there were not an infinite number of Protestant gentry in County Tipperary; Waterford is only about 50 miles from Golden, and some members of the Archer-Butler family held lands of a size similar to the Creaghe family during that time in Clanwilliam.

I am not aware of how common it was for a 19-year-old woman to marry a man literally twice her age in the 19th century, but it seemed to have worked out pretty well.

Anna Maria brought a connection to one of the most distinguished families in Ireland: Butler. ( See Appendix) The Butler name has been in Ireland almost as long as the Creaghe name. The Walter (? Fitz Walter) family arrived in Ireland in the latter half of the 12th century as a part of the Anglo-Norman invasion instigated by Henry II to get back into the good graces of the Pope after the 1170 murder of Thomas Becket. The plan was to civilize the Irish and the Anglo-Irish, who had gone native, and reestablish the Catholic Church on the troublesome island. The accomplishments of Theobald Walter led to Prince John, who at the time was in Ireland leading the English effort, to grant him the position of “Butler” to Ireland; henceforth, the family name Butler. One hundred fifty years later, James Butler was made the 1st Earl of Ormonde in 1305.

While our family has long enjoyed the cachet of being directly related to Thomas Butler, 10th Earl of Ormonde, the direct line goes back even further to Thomas’s grandfather and father: Piers Butler “Red Piers” (1407-1539), 8th Earl and James Butler “The Lame” (1496-1546), 9th Earl of Ormonde.

Thomas Butler (1531 or 1532 – 1614) became the 10th Earl of Ormonde on October 22, 1546, when his father was poisoned. By this time, the family had followed the Tudor path to Protestantism and the Anglican Church of Ireland. Thomas was a very loyal subject of the English Crown. In fact, he spent much of his youth in England and was more or less raised with a fourth cousin, Elizabeth. They were related through her mother, Anne Boleyn. The two became very close lifelong friends. When she became Queen Elizabeth I, Thomas held various positions in her court and was a close advisor. He was involved in various military campaigns for the Crown, in which he earned the nicknames Black Tom or The Black Earl. One of his battles was the one referred to in “A Great Feud and Its Ending” under the CFHS website “Family History”. Thomas was referred to in the article as the “chief of the Butlers”. There were several conflicts in “The Great Feud”, here referred to as the Desmond Rebellions, which were both a family feud between “old Gaelicized English families” [Butlers and Fitzgeralds (Geraldines)] and partly the Tudor efforts to Anglicize the Irish.

It seems the 10th Earl was “a man of many loves” with perhaps four legitimate children from one of three wives. He also had at least twelve illegitimate offspring. His acknowledged favorite among these twelve was our ancestor, Piers FitzThomas Butler (1554-1601). The prefix “Fitz” meant “son of” and was commonly applied by royalty and nobility when they wanted to acknowledge an illegitimate son (and was also used for legitimate sons). Presumably, the Earl named him after his own grandfather. His mother is officially unknown.

However, as Lord Dunboyne puts it:

“Indeed, there is not lacking circumstantial evidence to support the persistent and rather startling rumor that the Virgin Queen bore him Piers Butler of Duiske, the father of the 1st Viscount Galmoye. She and Black Tom were lifelong friends. Towards the end of 1553, she had the opportunity to conceive Piers Butler; in February 1554, she was said to be pregnant at Ashridge. In May, when offered physicians at Woodstock, she announced, ‘I am not minded to make any stranger privy to the state of my body but to commit it to God.’ She is said to have called Black Tom her ‘black husband’, and his will so favored his eldest illegitimate son, Piers, as to suggest that the mother of Piers of Duiske was someone of great importance.” (Dunboyne)

Patrick Creaghe recalls hearing the same story from a tour guide at Kilkenny Castle in 2007. It is also mentioned in genealogy book by Helen Gordon Moore and was noted by James Corning as coming from a family tree by Percy Creaghe. The document has been lost.

However, Elizabeth was more or less imprisoned from late January 1554 until April 1555 under suspicion (with good reason) of being involved in a plot to overthrow her half-sister, Queen Mary. In fact, she was confined in the Tower of London for the months of April and May of that year. Prior to her imprisonment, the twenty-one-year-old had been ill for at least a month and continued in ill health for over a year with diffuse pain, edema of the face and extremities, and swelling of her abdomen. Many observers commented on how ill she looked; some commented on the appearance of jaundice. At that time, there were rumors and speculation that “she was pregnant, near death, nothing could revive her, she had been poisoned”. (Erickson) She was attended by doctors at Queen Mary’s orders throughout and was constantly under the supervision of officials loyal to the Queen. It seems very unlikely that a secret pregnancy, birth, and slipping an infant away could have been carried out under these circumstances.

Would it not be most interesting if it were true? But then, we still do not know who Piers’ actual mother was. So, maybe?

Piers was granted the lands of Duiske Abbey. These lands had previously been confiscated by the Crown and then given to Thomas by Queen Elizabeth in 1576. The Earl then conveyed them to Piers in 1597. Piers went on to establish the Bansha Branch of the Butler family. Both Bansha and Duiske are ninety kilometers and twelve kilometers respectively from Golden.

The Earl lived most of his life at Carrick Castle, less than 50 miles from Golden. He built a manor house next to the castle in hopes of hosting Queen Elizabeth, but that never came to be. He died there in 1614, a venerable patriarch. He was buried in Kilkenny at St. Canice’s Cathedral, along with other Earls of Ormonde.

Although Thomas did not use it as his primary residence, Kilkenny Castle was the Butler Family Seat for centuries from the time the 3rd earl, James, bought it in 1381 and it was in the family until 1967, when the 24th earl sold it to the Castle Restoration Society. It is one of the best-restored castles around and well worth the visit.

Piers married Catherine (or Katherine) Fleming. Five generations later, Eleanor Butler married Thomas Archer. Their child, James Archer-Butler, followed. Compound names were and are common when a family wants to preserve a distinguished name or define an inheritance. James’ son was Piers Archer-Butler (1758 – 1827). This Piers married Anna Maria Gallwey. Unfortunately, we only have this low resolution image of Miss Gallwey.

Pier’s death was announced in the Belfast Commercial Chronicle:

“At Aherlow Castle, after a short illness, Pierce [Piers] Archer-Butler, Esq. He was twice High Sheriff of County Tipperary, a magistrate of independent principles and as kind-hearted gentleman as only in existence.”

Their daughter was our own Anna Maria Archer-Butler. She and Richard F.H. Creaghe were married in 1842 in Waterford.

The portrait miniature was attributed Adam Buck (1759 – 1833) of Dublin, who worked sometime before 1795 and stopping in 1833. Therefore, Richard could not have been more than 29 years old.

After their marriage, Richard and Anna Maria lived variously in Waterford at Blenheim House, in Clonmel at Ashborne House, and in Tranmore near Waterford to the south (James Corning).

It is not clear just what the basis of their income was during their married life. He did have a significant inheritance following his father’s death in 1837, but not as much as it could have been. Even though Richard’s older brother by seven years, Laurence, was living, Richard D.L.’s will stipulated that Richard F.H. receive Castlepark, Sargent’s Lot, Persse’s Lot, plus £3,183, unless Laurence was able to come up with over £9,000 that his father had loaned him in the past. Percy Creaghe speculated that if he was unable to provide the funds, he would receive nothing. Somehow, Laurence found the money, paid brother Richard, and came into possession of Castlepark and at least some of the other properties. In 1850, all of the previously mentioned properties plus one called Clogleigh (which I have not been able to locate, but there is a Cloughleigh just south of Golden ), were owned by “Creagh”, perhaps all by Laurence. (Marnane) In 1870, Richard Creaghe of Millbrook was reported to own 453 acres in County Tipperary. It does not indicate how he obtained the property — inherited or purchased. Millbrook is well north of Clonmel. A notice of the marriage of Richard’s son, Richard Fitzroy, in 1874 states that the groom’s father was from Athassel Grange, Co Tipperary. Grange Village is only a few miles east of Clonmel. Perhaps this is another property. The article describing Anna Maria’s funeral mentions a tenant from Athassel in attendance, implying ownership by Richard. The photo below is labeled “Creaghe House” in Orange. This probably an error and is actually Grange. Wouldn’t it be nice to know who the people are in the photo? Does the house still stand?

However, the £9,000 pounds was a significant sum (perhaps as much as 3.2 million dollars today — difficult to know). Richard’s family should have been comfortable. Also, Anna Maria may have brought some money in to the marriage, and Richard may have received some retirement pay from the army.

Their nine children were born over a 15-year period from 1844 to 1859. It is known that St. George Creaghe was born in Clonmel in 1852 and, presumably, they were living there when at least some of the other children were born.

)

This photo of Anna Maria was taken later in life and perhaps represents the height of fashion.

This photo is annotated as being from 1873. Richard would have been 69 years old at that time. If the 1873 is true, he looks to be in great shape for his age. I believe the date is incorrect. Also note the badge on his coat.

This picture was taken later in life, probably in his last decade. In 1871, he obtained a license for a black-and-tan male sheepdog in Waterford. He obtained a second license in 1881 for a black sheepdog. The dog in this picture does not look to be all black. Assuming he had only one dog at a time, the assumption can be made that this photo was taken around 1880. It looks as though the same badge is present on his coat. Perhaps it is something related to one of his regiments.

Whatever the financial situation may have been, it was not enough to ensure a livelihood for all seven of his sons. There must have been difficult discussions around this situation. The writing was certainly on the wall. The political and social situation in Ireland was quite unsettled, and the future of the Landed Gentry was not looking good. Many of the political changes, if not directed at the landowners, were affecting them directly. The previously oppressed, to grossly understate the situation, Catholic population was finally gaining power. Land reforms and redistribution of land were being agitated for at the time, and movement toward independence was beginning to grow. All of this, plus the math of dividing the estate between, at the time, seven sons and providing dowries for two daughters would have caused concern for Richard and Anna Maria. Fortunately, they had the foresight and means to address this early on. Of course, we do not know all that led to those momentous decisions that resulted in five of the six surviving sons to leave home for an uncertain future.

Richard Fitzroy and Harry Allington emigrated to Australia. Richard went first (age and date of departure are unknown at this writing). Harry followed in 1865 at age 16. Richard was no more than 21 when his younger brother arrived in Australia. The fourth and sixth sons, St. George and Gerald, left for the United States in 1874 at ages 22 and 18. Imagine sending off your sons — boys, really — knowing you would probably never see them again, ever. The only one to return briefly was St. George in 1884.

Richard was a Freemason; his home lodge was the Tipperary lodge in Clonmel. This was important to him in that he made arrangements for a dispensation to allow his son St. George to become a Mason and member of that lodge before he was the required 21 years of age and left for the United States. St. George remained a Mason until his death in 1924.

The fifth son, John W.W., went to sea some several years before the age of 21, but his home port was always in Great Britain and allowed him to return home from time to time.

Philip, the third son, remained in Ireland and was always near his parents’ home. Percy, the youngest child, died at age 13 in 1872.

The two daughters, Florence and Matilda, married into the Going and Cobdan families respectively and remained in Ireland.

This photograph was taken well after the expatriate boys had left and possibly after Richard died in 1890. However, the photo has a possible date of 1888 and the names do not all add up. The picture is presented as annotated; it is all the information we have.

” From left to right: J.W.W. Creaghe, Anna Maria, Philip. Seated in front of Philip, his wife Isabelle Emily and probably daughter Phyllis. Next, Florence Creaghe Going holding a child, perhaps Bena. Standing, Matilda Creaghe Cobdan. “

In this photo taken at the same time as the above, Anna Maria appears to be alert, happy, and healthy.

Richard and Anna Maria had long, full lives with every bit of their share of tragedy: Three of their children preceded them in death. Richard died on February 12, 1890, at almost 86 years of age at Melbrooke, near Clonmel. He left effects totaling £3,147 to Anna Maria.

According to an obituary found in an unknown Irish newspaper by James Corning, Anna Maria died unexpectedly after a short illness on August 12,1903. The suddenness shocked her family. At the time of her death, she was spending the summer season at Tranmore, a seaside town just south of Waterford on the Irish sea. Her fulltime residence was Ashborne House, Clonmel.

Some days later, her procession and funeral, those of a “much esteemed woman,” were held. The deceased and an assemblage of family left Tranmore for Waterford at 8:00am by road. The coffin was of “Irish oak with massive brass mountings.” A plaque affixed to the coffin was inscribed:

Anna Maria Creaghe

Died 12th August 1903

Aged 80 years

As the procession arrived and passed through the streets of Waterford, businesses closed, and blinds were drawn in private homes out of respect. By 10:20, the coffin and mourners were on the train to Cahir. On arrival the coffin was on a bier drawn by two horses and then bedecked with so many floral arrangements that it was completely obscured. Among those giving wreathes were daughter Florence Going; sons, Philip Creaghe and his sons Percy and Hubert, the Cobdan family; Captain John W.W. Creaghe and wife Julia; St. George and his sons, Gerald, Dick, And Larry. Also, one Agnes Dawana, a “faithful maid,” contributed a wreath.

The gathering then proceeded to Golden and the Anglican church and cemetery. Among those who met the coffin at Cahir and joined the procession were “tenants on Mr. Creaghe’s property, …Hogan from Athassel, Mr. O’Dea, Mr. Dunphy” were seen. This confirms that Richard held property in the Cahir-Golden area; just where is not clear. Whether this was a genuine show of respect, or whether it was expected is not known. Perhaps it was both.

At the entrance to the village of Golden, the procession was met by a “body of the R.I. C. [Royal Irish Constabulary] who then transferred the coffin into the church and, later, bore it to the nearby family vault. This token of respect was greatly valued by the family.

The official mourners were Philip Creaghe, Captain John W.W. Creaghe, Lieutenants Hubert Creaghe, Gough Going, and Hugh Cobdan; Captain George Cobdan; Coronel J. Arthur Pendergast (a cousin); and Mr. Hougomont and Mr. J.P. Cobdan. There were at least 100 other mourners mentioned. We can assume Richard and Anna Maria were respected and held in affection by their community and family.

Anna Maria left an estate valued at £5,791 to son Philip Creaghe and daughter Florence Going. Both Richard and Anna Maria were interred at the Creaghe Family mausoleum in Golden.

Stephen B. Creaghe, April 25, 2022.

References

Ancestry: Documents, Relationships, etc.

Creaghe, Percy, Creaghe Family in Ireland – Papers of Percy F.S. Creaghe, CFHS website.

Corning, James, Creaghe, Butler, Blunden and Other Related Names in Ireland, ca. 1980. CFHS website.

Dunboyne, Patrick Theobald Tower Butler, Baron, Butler Family History, 2nd ed., Kilkenny. Rothe House.1968. Available online.

Erickson, Carolly, The First Elizabeth, St. Martin Griffith, New York, 1983.

National University of Ireland, Galway, Landed Estates Database, Creaghe (Castlepark).

Marnane, Denis G., Land and Violence. A History of West Tipperary from 1660. 1985.

Wikipedia: Earls, Castles, Queens, etc.

Appendix

Creaghe Family relationship with the Butler and the Earldom of Ormonde

Piers Butler (1467-1539)

8th Earl of Ormonde

↓

James Butler (1496-1546)

9th Earl of Ormonde

↓

Thomas Butler (1531-1614) + Unknown

10th Earl of Ormonde

↓

Piers FitzThomas Butler (? – 1601)

↓

Sir Richard Butler

↓

Piers Butler

↓

Theobald Butler (d. 1671)

↓

Piers Butler

↓

Elinor Butler + Thomas Archer

↓

James Archer-Butler (d. 1814)

↓

Piers Archer-Butler (1758-1827) + Anna Maria Gallwey

↓

Anna Maria Archer-Butler (1823-1903) + Richard F.H. Creaghe (1804-1890)

No Comments