08 Aug Richard Creaghe DL and Matilda Parsons Creaghe, Their Life and Times

Richard Creaghe, DL (?-July 7th, 1837)

Matilda Parsons Creaghe (1769-August 10th, 1835)

Their Life and Times

Photo Courtesy of Margaret (Creaghe) Stine

Richard Creaghe, known variously as Richard Creaghe of Castle Park or Richard Creaghe, DL, is important in that he reestablished our family in Ireland, led an interesting life in dynamic times, and we are all descended from him and his wife, Matilda Parsons. While much is not known, let’s see if an idea of what their lives were like, and who they were as people can be reconstructed.

Now, we don’t know for sure where or even when Richard was born, but some very good assumptions can be made. Evidence indicates that his father, John Creaghe, Richard (?-1792), was living on the very small Dutch island of Sint Eustatius from around 1758 until 1788. The island is part of the West Indies group, now Leeward Islands, in the Caribbean Sea. John was in the sugar industry in some capacity and apparently doing quite well. The opportunities for making money at that time were very real. In the 18th century, the British economic interests in the Caribbean were significantly greater than in the thirteen American colonies combined. “There was nowhere in the world where money could be made at such a staggering clip as the Caribbean” at that time (Philbrick, p. 201). His wife, Anne Heyliger (1747-1832), lived there also, or perhaps on one of the new nearby islands. Their marriage occurred in 1766 or 1767 when Anne was about 21 years old (Percy Creaghe Papers). Anne seems to have come from a distinguished family in the area and had property of her own (Tuchman, p.13).

It is reasonable to assume that Richard was born soon after the marriage and almost certainly on Sint Eustatius. This was all before the Germ Theory of Disease, and there is no reason to expect that care elsewhere would have been any better. Certainly, not worth the weeks or months it would have taken to go to America or Europe. Two sisters, Johanna (d.? 1792) and Hanna Margaret (d. 1858) were also born there, but their birth dates are not known. Richard is listed as the oldest (P.C. Papers).

Based on that assumption, Richard could have been as much as 9 years old when a small, but significant, event occurred at Fort Orange which guarded the roadstead at Sint Eustatius. The American Brig-of-War, Andrew Doria, approached and saluted the Dutch fort with a single cannon shot before anchoring. As protocol required, the fort answered in kind. This was significant in that this was the first time a foreign power recognized the new United States as a sovereign entity. The date was November 16, 1776 (Tuchman, p. 7). If Richard and his family did not witness the exchange, they probably heard it. Canon reports are very loud, and Sint Eustatius is a very small island. They certainly knew the governor, Johannes de Graaff, who ordered the return salute; he was married to a Heyliger-the daughter of Abraham Heyliger, himself a former governor (Tuchman, p.13)

There is no indication of what Richard’s or his sisters’ educations may have been. It seems likely that it occurred locally. Even though their parents had the means to send them elsewhere, there was no evidence to suggest it.

Now is a good time to explore just what religion – Catholic or Protestant – the family followed. In 1813 a neighbor in the Golden area, Denys Scully described Richard “as a convert Creole”. What he meant was that he felt Richard was a “person of European descent born in the West Indies” who converted from Catholicism to the Anglican faith. Scully further stated that Richard’s father, John Creaghe, Richard, “had lived and died a Catholic” (Marnane, p. 172). As we will see Richard lived and died a Protestant. So, when did conversion occur? Anne was born in 1747, possibly in Massachusetts. In the early years of the colony, Catholicism was actually illegal, but there were small pockets of believers. It was not until the 1770’s that they were tolerated and the first Catholic parish was not formed until 1789 (Wiki.). On her death, Anne was buried a Protestant. Also, the predominant religion in Sint Eustatius was the Protestant Dutch Reform Church. Perhaps this all led to children being raised Protestant. There were certainly advantages to being Protestant when Richard moved to Ireland in 1788.

It is clear that in the early 1780’s Richard’s parents were making plans to move to Ireland in that John purchased the Burren Estate in late 1784 or early 1785. This was to become their future home, Castle Park (P.C. Papers).

Based on a letter addressed to him on 31 July, 1788, John was back in Limerick by that time. Six weeks later he took a Test Oath at the General Assize (court). This was an oath of allegiance required by law. It is not clear to me if it was required of everyone or just clergy and office seekers. It is also not clear just how anti-Catholic it was at that time. In the past, it was meant to exclude Catholics from those positions. At any rate, he took it.

Anne remained in Sint Eustatius until 1789 to dispose of property, including slaves, prior to the move.

We can assume that Richard, now no older than 22, accompanied his father, and we know that he received a commission as a Coronet in the 7th Dragoon Guards, British Army, on April 13th, 1788. This commission for the lowest rank of officer in the British Cavalry was purchased for him by his grandfather, Richard Creaghe, for £1,259.16.8 (P.C. Papers). Perhaps this was in the works before they sailed for Ireland. One wonders if John had cash flow problems since he had just purchased an estate and was planning a fine house. Or, perhaps, it was a loan to allow Richard to expedite the process. Regardless, this is the first record we have of Richard Creaghe of Castle Park at all (P.C. Papers). Purchasing a commission was a quite acceptable and common way for a young man of means to become an army officer.

The regiment was reorganized from a cavalry unit to the 7th (The Princess Royal’s) Dragoon Guards the same year Richard joined. Fortunately, the unit did not deploy from Great Britain during his time with it. Incidentally, Princess Royal was the eldest daughter of King George III who was well known to all Americans (wiki.). Nothing else regarding his army career is known other than his commission as a lieutenant on January 13th, 1791. He received a letter addressed to Lieutenant Creaghe, 7th D. G. on December 2nd, 1793 (P.C. Papers). It is reasonable to speculate that his time with the army spanned at least four years and eight months from April, 1788, until his father’s death on December 2nd, 1792. Probably Richard resigned his commission about that time to take over Castle Park and manage the completion of the house which was achieved in 1795. Until that time he resided at 8 Great George Street, Dublin. His furniture was moved in May, 1795, and Richard was receiving mail at Castle Park by December of that year. He lived there until his death 41 years later.

In this timeframe, Richard, approximately 27 years old, married Matilda Parsons of Parsonstown, Kings County (now Birr, County Offaly) on July 5th, 1793. This union was one more example of Creaghes “marrying up”. The Parsons were a distinguished family of English origin who settled in Ireland in the late 1500’s and produced various Baronets, Viscounts, Earls, and members of the Irish Parliament over the years as the family’s fortunes and favor waxed and waned. Matilda’s first cousin, Laurence Harmon Parsons, was First Baron, then Viscount, and finally the Earl of Rosse in 1806. He also sat in the British House of Lords from 1800 to 1807, as one of the original Irish Representative Peers (Wiki.). The Earl’s family lived in the Birr Castle in King’s County (now County Offaly), which was next to Tipperary on the north.

It is probable that Matilda’s immediate family did not live in the castle per se, but it seems reasonable that she must have at least visited. Perhaps, she and Richard were guests from time to time. One does wonder how they met in that Richard spent little, if any, time in County Tipperary before their marriage in 1793 in Dublin.

The Parsons family was Protestant as evidenced by the fact that the family seat, Birr Castle, which they had held since 1620, was besieged by Catholic forces for over a year in the Rebellion of 1641. The family castle was in King’s County (now County Offaly) which borders Tipperary to the north. Incidentally, Birr Castle, is still owned by the family and, as of October 23rd, 2016, was the home of the seventh Earl of Rosse, William C.L.V. Parsons (Wiki).

Presumably the couple resided at Great George Street although Richard spent time with his regiment. Based on Google Maps Street View, the town home is a substantial four-story structure – certainly not small. The top floor has smaller windows and may have been servant’s quarters.

Also, living in the home were his widowed mother (Anne) and his two younger sisters, Johanna and Hannah. Johanna died before Richard’s marriage in 1792 at age 22, soon after they moved in. Hannah had not yet married (P.C. Papers).

The family dynamic must’ve been interesting with all those people living under one roof. Add to that, the birth of a baby, Elinor, born to Richard and Matilda June 16th, 1794. There is evidence that they shared expenses for 1792 and 1793 (P.C. Papers).

Presumably at least Richard and his family, along with his mother, moved to Castle Park in 1795. It is not clear if Hannah joined them there. It is clear that Richard was not getting along with his mother or sister by this point. As Percy Creaghe puts it, Richard and Anne “fought like blazes over the [John Creaghe, Richard’s] will, and very probably about her being turned out of Castle Park.” This rift became more apparent when she wrote her own will in 1829 specifically leaving her son “NIL”. The bulk of the estate went to her daughter, Hannah Margaret Alen (£3,300 – £3,700) and her children (over £5,000). Richard’s wife Matilda got £100 and another £2,700 went to his children. Richard was not pleased, and made efforts to obtain more. He was not successful (P.C. Papers).

It seems Richard also had issues with his surviving sister, Hannah. Their mother, Anne, did not approve of Hannah’s prospective husband, Luke Alen, and in 1798 asked Richard to do what he could to block the marriage. He replied, “I don’t give a Damn what she does.” One of the executors, James D. Michael, commented that Richard “really ought to be nicer to his mother” (P.C. Papers). Family relationships can be remarkable things.

Evidently Richard and Matilda settled in at Castle Park where they went on to have nine children between 1794 and 1809, eight of whom survived into adulthood.

To try to appreciate what their lives were like over the 40 years they lived at Castle Park, some effort must be made to understand the Irish history of the 18th century. These were not smooth times; conflict was the order of the day. While I find it quite complicated, the situation can be understood as three basic ongoing, evolving, often intermingling conflicts:

Land: Peasant versus Landlord.

Religion: Catholic versus Protestant.

Political: Independent Free State versus maintaining ties with Great Britain.

At one time or another each of these three points of contention rose to the fore, but there was always a mixing of the three at any one time. Additionally, there would commonly be fractional disagreements within the various subgroups that would erupt into violence. It can be confusing, but the main driver during Richard’s time was competition for land with an increasing population. The fact that most, but not all, of the peasant class was Catholic and most, but not all, of the landed class was Protestant complicated the matter (Marnane, Cruise O’Brien).

Having access to land was a matter of actual survival. The diet of the laboring class was almost exclusively potatoes and milk. Crop failure with resulting famine was not uncommon. The Great Famine of 1848 was the worst, but certainly not the only one (Marnane, p. 41).

If one had less than five acres of tillable soil, there was “a distinct possibility of disaster” hovering at all times. Five to 15 acres held “promise of survival in times of a poor harvest” (Marnane, p. 41). The more you had, the less likely you were to be affected.

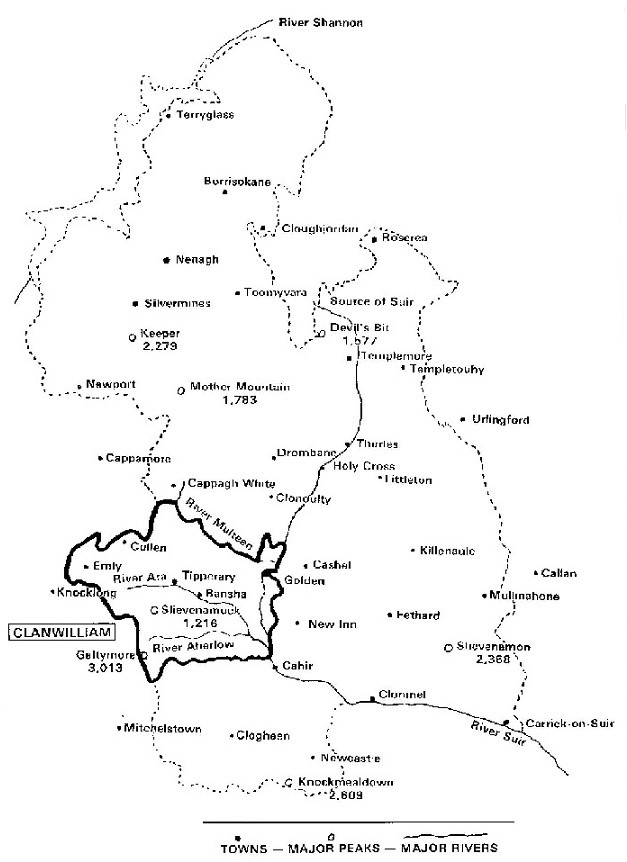

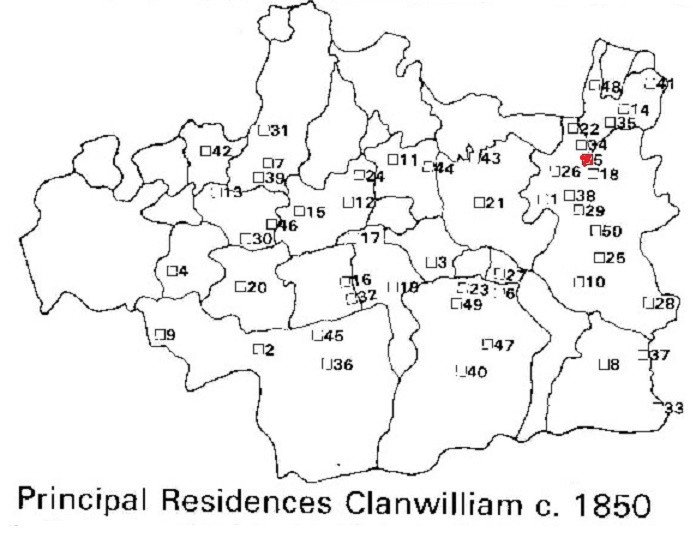

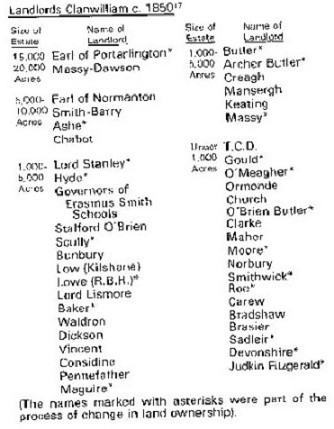

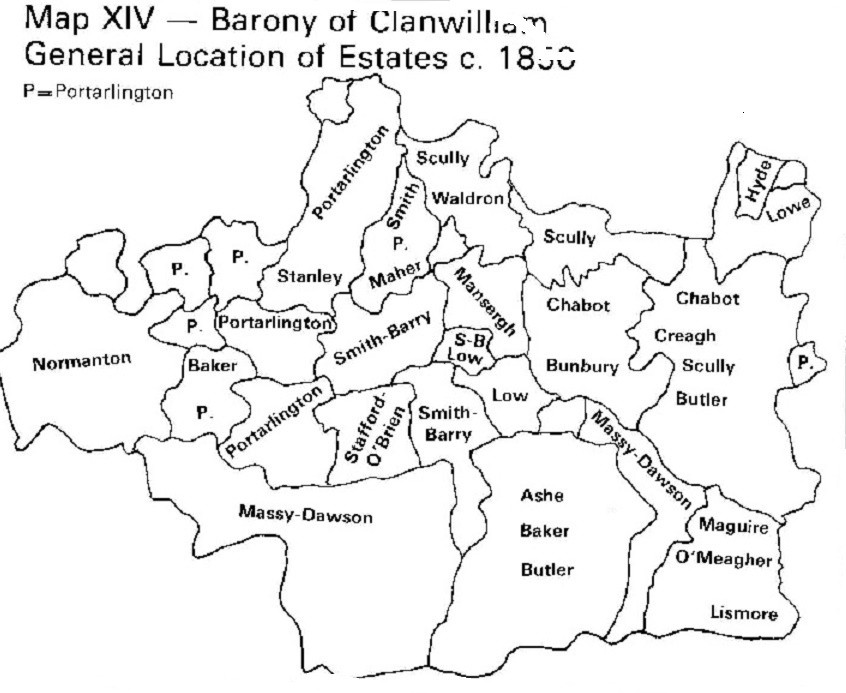

Castle Park was listed at being in the category of 1,000 to 5,000 acre estates (Marnane). Liam Maher, the current owner of the property where Castle Park House stood, told Lucy (Corning) Brackett in 2016 that he believed that the estate was approximately 2,700 acres. A compilation of land ownership in West Tipperary (Barony of Clanwilliam) shows a total of 2,214.75 acres valued at £1,708 (Marnane, p. 149). It can be concluded that Richard and his family were in the strata of society that was never at risk of starvation per se.

Another indication of where the family stood in the Clanwilliam society can be extrapolated from the 1841 census data regarding the types of housing in the Barony.

Class Four: Mud cabins of one room (thirteen-percent were shared by more than one family).

Class Three: Mud cottages of two to four rooms with windows.

Class Two: Good farm or townhouses with up to nine windows.

Class One: All those superior to Class Two.

Of Clanwilliam’s 52,430 inhabitants, 84.6-percent lived in Class Three or Four mud dwellings. The poverty in which these people lived cannot be overstated (Marnane, p.51). As can be seen by the photo below, the twenty-eight room Castle Park House was a Class One dwelling.

Obviously, our family lived in the top strata of housing. Living in a Class One or Two house was also an indicator that the owners would not have seen famine as a life and death struggle. In fact, in the early 1840s, Richard DL engaged the architect William Tinsley to remodel the home at Castlepark.

However, it is also easy to see how tensions can grow between a large, repressed, sometimes literally starving, impoverished, mostly Catholic majority and a small, privileged, comfortable, land-rich, mostly Protestant minority.

The pressure for land was the driving force for the unrest in rural Ireland during Richard’s time – the first half of the 19th century. Tipperary was intimately involved in the violence of that period. In fact, “the lawlessness of the Tipperary region was its chief claim to fame in the decades before The Great Famine [1848]” (Marnane, p. 41). “Golden itself was known as one of the most disturbed places in Ireland” (Marnane, p.49). The violence was characterized by sporadic agrarian terrorism such as savage beatings, murder of families, destruction of property, and occasional widespread frank rebellion (1814-16, 1821-23, 1831-34); all of which were related to economic conditions. Typically, there would be a peasant (Catholic) action and a gentry (Protestant) reaction (Cruise O’Brien, p. 97).

The family entered this arena in 1795 when Richard, Matilda, and one year old Elinor moved from Dublin to Castle Park. Over the next 12 years another eight children were born – one of whom died in infancy. That must have been an active household. Unfortunately, we know nothing about what their day to day lives were like.

What we do know is related to Richard directly. Presumably, he resigned his commission in the British Army on moving to Castle Park in 1795. By October 31st of the next year, he was a Second Lieutenant in the Ballintemple Cavalry, rising to First Lieutenant in less than two years on August 23rd, 1798. He may have risen to Captain, but there is no documentation (P.C. Papers).

So, what was the Ballintemple Cavalry? It was a part of the British-controlled Irish Army, but more of a militia. These units were predominantly Protestant, and as a rule, were used to maintain law and order: the status quo from the point of view of the landed class. Ballintemple was a parish near Cashel, a little north of Golden (Wiki).

In the latter part of the 18th century, Ireland was governed by a quasi-independent Irish parliament. However, it was clear who was really in charge in that the “actual administration remained in the hands of the Lord-Lieutenant appointed by the English government (O’Brien, p. 87). Significant portions of the Irish population were not satisfied with this arrangement, certainly not the severely repressed Catholics and their Protestant supporters. The merchant class, which was both Protestant and Catholic, was particularly unfairly treated by the system.

Add into this mix the American and, particularly, the French Revolution, and a rebellion can and did result. The resulting movement evolved into a desire for an Irish republic based on French principles. The insurrection broke out in May of 1798. It was somewhat widespread, but not coordinated, and was put down “with great severity” (O’Brien, p. 91). It was over in four months.

Tipperary was not directly affected, but there was significant unrest. Even before the actual rebellion in March of 1798, a “thousand country people…marched into Cahir [just south of Golden] and proceeded to search for arms” (Marnane, p. 33). This was put down by the Irish Army. There is no evidence that the Ballintemple Cavalry was involved, and the Castle Park area was not directly affected. However, they certainly knew about it.

One of the reasons the rebellion did not spread into Tipperary was in part credited (or blamed) on the High Sheriff of the county, Thomas Fitzgerald, a ruthless and fanatical loyalist. “The gentry and mobility had good cause to regard their High Sheriff as their savior” (Marnane, p. 34). It also demonstrated the potential power of the office of High Sheriff. Even though they were new in the area, there was a good chance they knew this man.

The short, unsuccessful rebellion resulted in the “Union”: The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland on January 1st, 1801.

By this time, Richard and Matilda were the parents of four children – Elinor, John, Laurence, and Anne Matilda – ages 6 and a half to 2 years. In October, their fifth child, a boy, Francis tragically died at 3-months of age. More than likely this was from an infectious disease that would not have been an issue today. Childhood mortality was higher in those days; and, to a certain extent, expected. Still, this must have been a blow.

As a generalization, 19th century national politics hardened into the pattern that would persist until “The Rising” of Easter Sunday, 1916. This ignited a guerilla war that eventually led to the Independent Irish Free State in 1921. Again, in general it was Catholic “Home Rule” or “Sinn Fein” versus the Protestant “Unionists”. In fact, by 1820 the Protestants were seen as “England’s garrison in Ireland” (Cruise O’Brien, p. 99).

In the countryside – Tipperary in particular – the violence was characterized by peasant action and gentry reaction driven by economic considerations and the shortage of land. This was the predominant source of unrest that underlay the rest of Richard’s life. It can be inferred the family was in the Protestant, landowner, loyalist camp based on the positions he went on to hold.

In 1803 his military experience again came to the fore when he personally raised an Infantry Corps of Yeomen (farmers, small land owners) volunteers: The “Loyal Golden Infantry”. Naturally enough, Richard was commissioned Captain Commandant on October 15th, 1803. This would imply that Richard was a man of means and that he could provide at least some of the funds to support this unit. Apparently, they had some type of uniform upon which there were silver buttons embossed with “a turret castle surmounted with royal crown within a ribbon inscribed “Loyal Golden Infantry” (P.C. Papers).

We know the unit was still active seven years later, with Richard in command, from the Golden Church records in 1810. He was chosen by parishioners to be elected church warden, an important lay position. However, the rector, Mr. Hare, stated that he considered Richard to not be “a proper person to be a church warden. “He did muster and exercise his yeomanry during the hours of divine service on the Sabbath Day and also that he was on the Sabbath would report him to the Bishop of Cashel for his conduct” (P.C. Papers). The Bishop’s response is not known.

By this time four more children had been born into the Creaghe family – Anne, Richard, Stephen, and Elizabeth. The household now held eight children, 19 to 6 years of age. It must’ve been a remarkably active place. It is reasonable to assume that a household staff of some extent was also present; labor was not expensive. Castle Park must have been a great place to be a child: horses, other animals, fields, a river.

However, it was not all peaches and cream in that there was always the threat of violence overshadowing the lives of the landed class. There is no evidence that Castle Park was ever the target of marauders, but “homes of neighborhood gentry were increasingly subject to attack by armed bands in search of more arms. This caused considerable assault on their sense of security” (Marnane, p. 47).

As previously discussed, there were three major outbreaks of violence during Richard’s lifetime: 1814-16, 1821-23, and 1831-34. In the middle of the first, he was appointed High Sheriff of County Tipperary by King George III for the customary one-year term. (Interestingly, he was succeeded by Piers Archer-Butler who was to become the father-in-law of Richard’s then 12-year-old son, Richard Fitzroy Heyliger Creaghe.)

Being appointed High Sheriff in Ireland in the 19th century was not a trivial thing, but along with the honor came responsibilities. The honor part was due to the fact that the office was granted at the highest levels: The Crown. The responsibility part of the annual appointment was significant. He was a sovereign’s judicial representative in the county, and with that came the requisite ceremonial and administrative duties. Most importantly, the Sheriff was responsible for the preservation of law and order (Ball, p. 1) in County Tipperary. The preservation aspect was, of course, from the point of view of the establishment: Landed gentry, Protestant faith, and the Crown. These duties represented a challenge in Tipperary at that time.

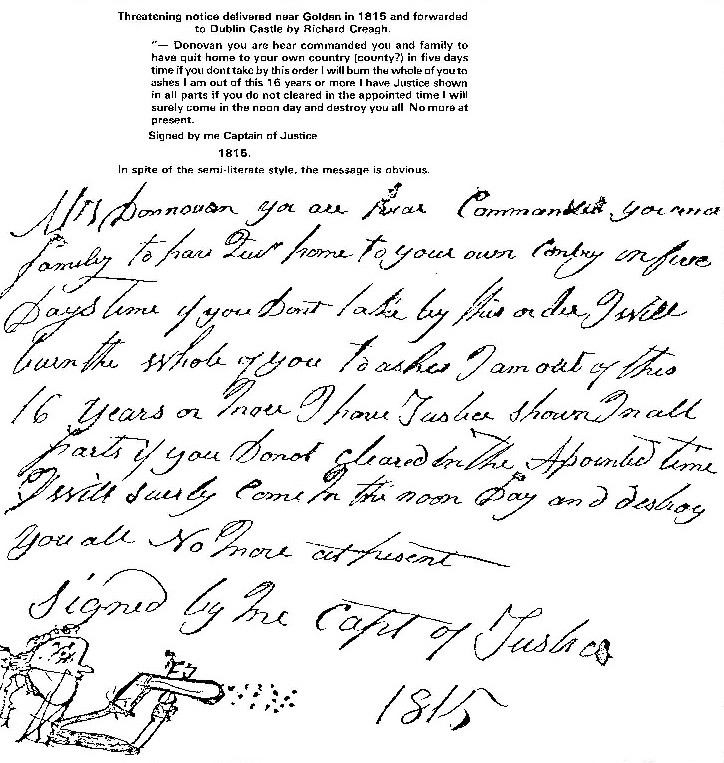

An incident typical of the times occurred in May, 1850. A riot broke out at a Fair in Golden in which two men were killed. It is not clear what motivated this violent event, but the tension of the time was certainly a contributing factor. It is likely that one of the instigators sent a threatening note to Mr. Donovan who lived near Golden.

Mr. Donovan was concerned enough to pass it on to the High Sheriff. Richard then sent it on to the seat of the Irish government, Dublin Castle, probably as a request for assistance. (Marnane, p. 45).

It is apparent by another incident of the same year that the Loyal Golden Infantry was still in existence, and Richard was still in command. In those days, there was a circuit court which tried the more serious civil and, particularly, criminal cases. This court was referred to as the “Assizes” (wiki.). According to Percy, Richard “met the judges with his own troops at the boundary of the county” when they came to hold an “Assize” (P.C. Papers). It says something about the times that the judges would need an escort.

After Richard’s term as Sheriff, things calmed down somewhat in the area. However, he remained active. In September, 1816, he offered to mediate a disagreement between the same rector, Mr. Hare, who had admonished him for drilling his troops on the Sabbath, and his parishioners. Mr. Hare was again less then receptive to the idea of Richard’s involvement. In a notice to his parishioners Mr. Hare rejected the offer and urged the former High Sheriff to devise a plan to “stop or check the outrageous robberies and murders in the county” (P.C. Papers). There is no record of a response by Richard. Obviously, the violence continued.

One other factor contributing to the tensions of the time was that most, if not all, the small subsistence farmers held rented land. The rental terms favored the landlords; and, if the rent could not be paid, eviction followed. The primary reason for failure to pay was crop failure. There was not much of a safety net for these people in those days. The economic theory of the time, “The Manchester School” forbade “state interference with the working of economic laws” (Cruise O’Brien, p. 105). Church-funded “workhouses” and “fever hospitals” provided rudimentary relief for some (Marnane, p. 62).

There were episodes of crop failure or epidemic with resulting evictions during Richard’s time. But never on the scale of The Great Famine in 1848, when one-million Irish peasants literally starved to death. That came during son Laurence’s tenure.

On the social level, governments, economists, and the well-off segments of society “were inclined to regard the sufferings of the poor, of whatever nationalities, as part of the natural order of things” (Cruise O’Brien, p. 106). Richard and his family had nothing in common with the population that made up the 80-plus-percent of the population who lived in mud houses (Marnane, p. 162). They probably had no interactions with these people; Richard may have had an agent to interact with them and collect his rents.

Having said that, Marnane does not mention Castle Park as being a party to any tenant-landlord confrontations. One likes to think the best of one’s ancestors, and perhaps Richard was more enlightened than most. In his favor, he was an Irish landlord; not an absentee English landowner. However, his nemesis, Reverend Mr. Hare, was less than pleased. In his notice to his parishioners of September 16, 1816, he proposed a fund “for the relief of any of the tenants of any of the following resident landowners” and goes on to list Richard among nine other esquires, including a Scully and a Butler (P.C. Papers). So, was Richard any better or any worse than the other landlords? Probably not. In fairness, judgement should be made to some degree in the light of the times.

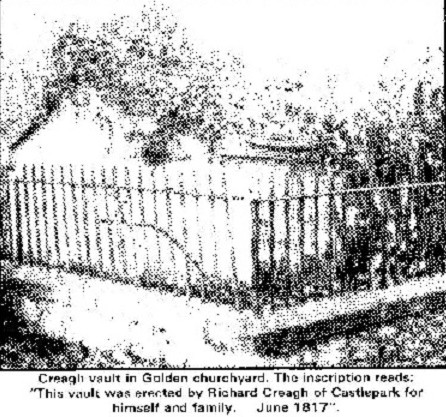

In May, 1817, tragedy again struck Castle Park with the death, at age 21, of John Creaghe, the first-born son and heir of Richard and Matilda. The cause is not known, but it was most likely infectious disease or trauma. John is not listed in any of the family sources as having been interred in the family vault in Golden. However, his death could have been the impetus for construction of the vault in June of the same year as his passing, 1817.

It is quite possible his remains are there – perhaps Francis also. The vault itself is an indication that the family “was well off” in that it is the only one in the church yard that is at least partially above ground (Brandon O’Riorden to LCB).

Four years later Richard was faced with a need for a considerable sum of cash to provide for his children. He mortgaged some of the estate for £5,000 (Marnane, p.97).

Also in 1821 there was another flare of violence in Tipperary, lasting two years. This, too, was characterized by attacks on the homes of the gentry by armed bands – sometimes quite large (40 to 50 men) – looking for arms. Again, there is no evidence that Castle Park was targeted, but it must’ve been at least somewhat unnerving for the family.

At this time, Richard was serving as a magistrate in the Golden area. In the summer of 1822, he wrote to his higher-ups in Dublin regarding government funds to reward a certain Peter Downing who was acting as an informant regarding unrest in the area. Richard had been funding Mr. Downing out of his own pocket and now wanted the government to step up to the plate. After two letters had gone unanswered, a third, with endorsement from two lords and a tone of injured pride, finally resulted in a payment of £5 to Mr. Downing for his efforts (Marnane, p. 47). We have an example of Richard’s signature, presumably from one of those letters.

In 1830, Richard and Matilda lost yet another child, 36-year-old Elinor. There is no evidence that she married and she is not listed as being buried in the family vault. Her parents were in their early 60’s at the time.

A third major outbreak of violence, along with the usual angst for the family, gripped the Tipperary area the next year and lasted for three years (1831-34) (Cruise O’Brien, p.97). In the midst of this, Richard was appointed Deputy Lieutenant for the County of Tipperary on November 3rd, 1833. This position was granted by the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, a personal representative of the Crown in the colony. While this position today is largely ceremonial and charged to “uphold the dignity of the Crown”, the 19th century Lord Lieutenant was head of the Irish government in Ireland. The Lord Lieutenant appointed deputies as needed to represent the office across the country; Richard was one of these. It is not known how long he served or specifically what he may have done in that role. With the “Uprising” and creation of the Irish Free State in 1922, the position was eliminated (Wiki.).

Richard, however, was entitled to add the post nominal letters, DL, to his name; hence, Richard Creaghe, DL. Prior to this, he was referred to as Richard Creaghe, Esquire or Esq. Qualifications for this designation may have been based on his being a magistrate, army officer, or member of the landed gentry (country squire). It was a notch above gentleman (Wiki.).

Other than the stint as Deputy Lieutenant, we don’t know anything specific about the last 15 years of Richard’s life. It can be assumed that he continued to actively manage the estate. Daughters Anne Matilda and Anne each married a Collins (Charles and William respectively) and together produced a total of six grandchildren, whom Richard and Matilda may have known. Laurence, may or may not have been married by then, and it is not known when his children were born.

Somewhere in this period, Richard must have loaned over £9,000 to Laurence. That would have been a very large amount of cash to come up with; perhaps it was the cash equivalent of something like land. Richard’s will was drawn up somewhere in this time, and stipulated that Laurence must remand that amount to his younger brother, Richard Fitzroy Heyliger Creaghe. If he did not, the estate went to brother Richard. Laurence came up with the payment, got the estate, and the rest is history (P.C. Papers). We are left to only wonder “what if?”.

Percy’s description may have been a simplification of the overall outcome of events related to the will. The foot notes from the “Creagh Family of Golden family tree” in Appendix VI of Marnane’s book indicates that Laurence inherited the Clogleigh property “in fee” and Richard Fitzroy Heyliger received Castle Park, Persse’s Lot, and Sergent’s Lot plus £3,183 (Marnane, p.171) Evidently, at least Castle Park and perhaps both the other parcels reverted to Laurence upon the payment to his younger brother. He details are not clear, but; they do exist – somewhere.

On August 10th, 1835, Matilda died at the age of 66 after 44 years of marriage and was interned in the family vault. Richard lived on for another two years. He died on July 26th, 1837, no older than 70. His death is listed as having occurred in Harrogate, England. This city was known for its mineral springs, and for centuries, the well-to-do came for the waters to treat their ills (wiki.). Perhaps this was what Richard was attempting. Since he was there, perhaps he was spared the knowledge of the passing of yet another child, Anne at age 34, only four days prior to his own death. Both are buried in Golden.

Richard and Matilda lived reasonably long, interesting lives in interesting times: the first part of the 19th Century in Ireland. The conflicts, tensions, travails, and politics set the stage for the defining struggle that culminated over 80 years later with the Irish Free State. Through all that, it seems Richard managed the estate well, and handed it over in reasonably good condition to his son Laurence and, evidently, some to Richard Fitzroy Heyliger Creaghe.

They had nine children and raised eight in their home, which must have brought joy. They also experienced the anguish of burying three children. Six went on to have families of their own.

In some ways, Richard and Matilda lived at the end of an era for landholding families in Ireland. After they passed, the social economic and political forces led to, if not exactly the demise, the great diminution of that way of life.

Stephen B. Creaghe, February 20, 2017

APPENDIX

All maps and tables from Marnane, Denis G., Land and Violence, A History of West Tipperary from 1660,1985.

Castle Park is Number 5

References:

Ancestry, various

Ball, Larry D., Desert Lawmen, University of New Mexico Press,1992.

Creaghe, Percy F.S., Creaghe Family in Ireland-Papers of Percy F.S. Creaghe, ed. Michael and Merril Barnett, CFHS website.

Cruise O’Brien, Marie and Conor, Ireland, A Concise History, Thames and Hudson, 1985.

National University of Ireland, Galway, Landed Estates Database, Creaghe (Castlepark).

Marnane, Denis G., Land and Violence, A History of West Tipperary from 1660,1985.

Philbrick, Nathan, Valiant Ambition, Viking,2016.

Tuchman, Barbra W., The First Salute, Knopf,1988.

Wikipedia, various subjects

No Comments